Snow falls softly on the trees surrounding Carol Waters’ tiny cabin near Maple City as we wait for her to answer our knock. I have never met this 82-year-old woman, who protected 15 acres here along beautiful Lime Creek some 23 years ago. But before I take my coat off, I find myself enveloped in a warm hug. There is a plate of freshly baked cookies on the table, and a teapot steams on the stove.

Conservation Easement Program Manager Yarrow Brown and I have come to hear the story of Carol’s changing landscape, and to learn about the relationship she has developed with the beavers who have transformed the ecosystem surrounding her home.

Carol’s love for nature began when she was a little girl, living downstate near Lake Saint Clair. She and her sister spent hours on the lake, ice skating in winter, swinging from a huge willow tree in summer. Her love for Leelanau originated during family trips to Glen Lake and later when she brought her own four children up from Detroit for vacations.

The former owner of the Lime Creek cabin and property was a friend of Carol’s from Detroit named Barbara Cruden. “I admired her so much,” says Carol. “She was a great mentor and naturalist and was always teaching me how to be a better observer on this land.” Over a 15-year period, the two friends would be involved in three Leelanau Conservancy conservation easement projects totaling 167 acres.

Around the time Carol had discovered the Lime Creek property, her life was changing rapidly. Her children were grown, and her 28-year-marriage had just ended. One day the phone rang, and it was Barbara, offering to sell her the cabin and surrounding land. Barbara had bought land on nearby Wells Lake, which had been protected by the Leelanau Conservancy. “My life had just broken apart,” says Carol, then 50. “I did a happy dance. It was perfect.”

She moved into the tiny cabin and spent her days wandering the property. During that first winter she parked her car just off the road and hauled supplies in by sled. Carol remembers star-filled skies and the utter peace of the land. “The earth teaches you, if you are open to it,” she says. In 1996 she worked with the Conservancy to permanently protect her land with a conservation easement. “I just felt it was really important because wetlands are the beginning of it all,” says Carol, who serves on the Good Harbor Bay Watershed steering committee. “If you don’t protect them, you can forget about the water quality of the lakes.”

It wasn’t until the last decade that the beavers arrived and built the first of two dams. Carol and a friend had noticed that the stream level kept fluctuating. They followed the stream toward her neighbor’s property, which grew deeper and wider, and discovered a tangle of mud, branches and rocks. Carol says that both she and her neighbor were “thrilled that the beavers were here.”

Since then, these industrious native creatures have been busy. The view out Carol’s southern window reveals a hillside once flush with poplars now dotted with stumps. Beavers chewed down dozens of trees; then slid or dragged them toward the stream. Eventually their construction created a large pond that in the process led to the demise of a stand of cedar trees. These nocturnal, herbivorous rodents create one or more dams to provide still, deep water to protect them and their kits from predators, and to float food and building material. A great source for more info on beavers and how they are being used to restore watersheds is the U.S. Forest Service: https://www.fs.usda.gov/features/working-beavers-restore-watersheds.

Beavers in North America once topped 60 million, but as of 1988 populations were estimated at 6–12 million. The decline is the result of extensive hunting for fur as well as removing beavers whose activities conflict with other land uses. Beavers use powerful front teeth to cut trees and other plants that they use both for building and for food.

Beavers can cause damage and are considered pests by some landowners and municipalities. On Carol’s land, they have caused the water to come a bit too close to her guest cottage along the creek. She enlisted Yarrow’s help and consulted experts from the Department of Natural Resources. Because her conservation easement provides for maintaining her existing structures, she had the right to remove the beavers or to disrupt their dams. But in the end, Carol says the beavers created a second dam and relocated, drawing water away from the cottage.

“I think they are good community members and they listened to our concerns,” adds Carol, noting that these creatures are so elusive that she rarely sees them. “I believe we can co-exist. The beavers have brought so many gifts. We now have heron and ducks, fish and lots of frogs and toads that never used to be here.”

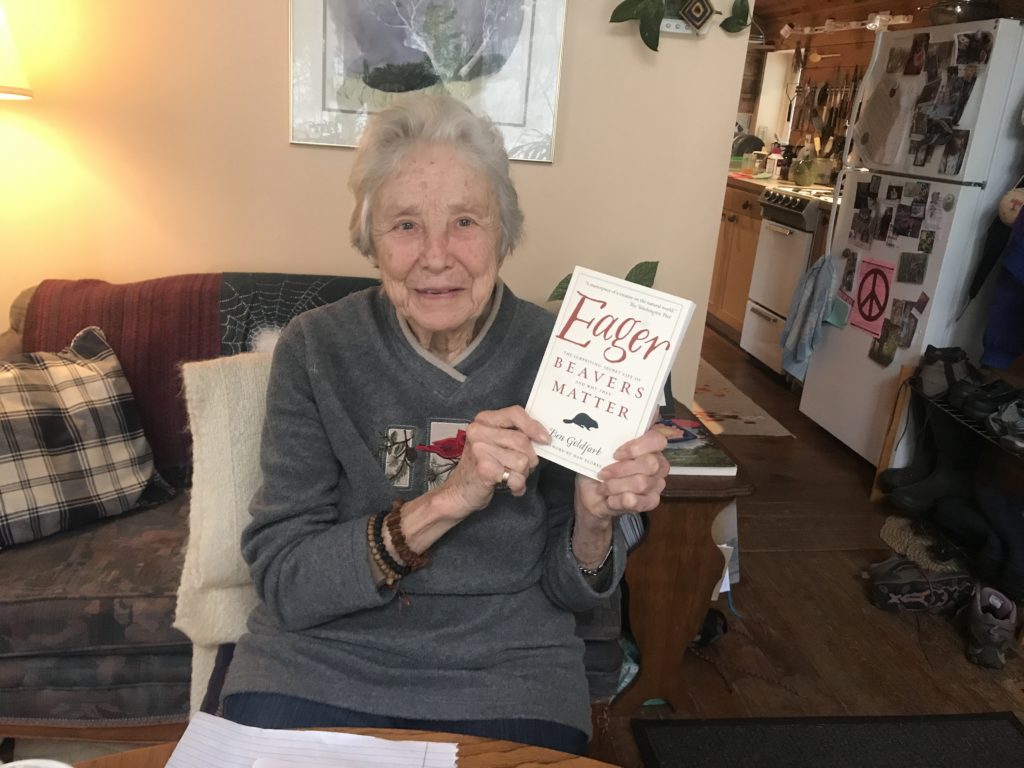

“Beavers are hydrological engineers,” she says, placing her hand on a book about beavers titled Eager by Ben Goldfarb that she refers to often. “They know how to spread water out and they shaped North America.” The book documents how beavers have been reintroduced in the West to help with water conservation efforts. It also notes that once beavers arrive on the scene, the habitat they create supports 80% of biodiversity. A group known as “Beaver Believers” contends that these large rodents can “right any environmental wrong. They can restore wetlands, heal lands compacted by grazing. They are a kind of magic helping to store water and sustain other creatures.”

“I just want to learn more about why they are here, and welcome them as a part of the landscape,” says Carol. “Eventually they will go where the food is and will move on. They are ecosystem engineers, spreading water, and we haven’t given them enough credit for that.”

On our way out the door, there are more hugs from this woman who doesn’t own a TV or a computer, who does not engage in social media and gets her news via a small radio. Ten words on a hand-painted plaque on the door sums up her philosophy: “Sing songs, plant seeds, pick weeds, make medicine, trust yourself.”—Story by Carolyn Faught. Published in the Leelanau Conservancy’s 2019 Annual Report.

Private Conservation Easements

As of the end of 2019, the Leelanau Conservancy has worked with over 180 landowners like Carol Waters to preserve over 10,000 acres of cherished family lands with conservation easements (CE). A CE is an individualized legal agreement designed to protect the natural features of land in perpetuity. A longstanding Leelanau Conservancy philosophy also provides that the CE must be good for both the land and the landowner. Collectively, these private lands are helping to protect Leelanau’s water quality, wildlife habitat and are to reduce the impact of climate change. Learn more about CE’s and read more landowner stories about people who have chosen to conserve their lands at LeelanauConservancy.org (search landowner stories.)